Depths of Dankai Part 1

"Dankai. How deep is the river?" We point at our chicken map and mime water depth on our bodies – hands at ankle level, thigh, chest, over our heads.

The three Tajik hunters look at one another, wrinkle their foreheads. Eddik, the largest of the trio, shakes his head and draws his hand across the air with his arm extended full stretch above his head.

I make round eyes at Chris and Michael. Chris shrugs. Michael pulls out his Russian phrase book. But phrase books don't include questions like, "Is the river fordable?" Michael returns his book to his pocket and we concentrate on our cups of milky tea in the unexpected luxury of the Marco Polo sheep hunting lodge on the borders of Lake Karakol, high in the Tajik Pamir.

***

It is 2015 and I've chosen to celebrate my 50th birthday in the mountains of Tajikistan. Why Tajikistan? It's actually my second choice after the Karakoram Highway (from China into Pakistan) proved unfeasible because China won't let people cycle to their border and there's only a week of cycling in relatively safe areas in Pakistan. A bus load of people, including tourists, had recently been executed by men wielding Kalashnikovs…I prefer an edge to my adventures, not diving over a precipice. In 2018, seven cyclists will be attacked on the Pamir Highway by Islamic State activitists – a car drives into them, men leap out and stab them. A young American couple die. Lucky that potential deterrent is still in the future.

As I search the internet for options beyond the Karakoram, Google proposes the Pamir Highway, or 'M41'. The Pamir Highway is the only continuous route across Tajikistan and Kyrgystan approximately following one of the old Silk Roads, from Dushanbe (capital of Tajikistan) to Bishkek (capital of Kyrgystan) along an old Silk Road route. I'd never heard of the Pamirs. Images of stark, snow-capped mountains, empty valleys, braided river plains, yurts and yaks filled my screen. That's my sort of place.

We select equipment and clothing appropriate for a remote location with few medical supplies, cold nights and no camping gas. We've been on a few challenging cycle tours, particularly western Xinjiang in China so we have background to draw on. We use our established approach to carry our loads – two large, waterproof panniers – German Ortleibs, the best!, a heavy duty tramping pack bungeed to a rear rack, and a handlebar bag. I specifically object to front panniers as I think having too much space makes you take too much stuff. Heavy bicycles are no fun.

We take our Trek Kobias with 29 inch wheels and front suspension bicycles. They've worked well so far. We book tickets through the USA and Istanbul and fly over oceans of gold and red desert to land in Dushanbe airport in the middle of a 38 degree Celsius afternoon. Exiting the airport we stagger; we hadn't thought it would be so hot so early in the summer, it's the beginning of July. On the gold and red tiles outside the concourse, we unpack our bike boxes , put gear in panniers, and donate our bike boxes to the first of the queue of the Tajik children who have watched us unpack. Then we cycle into the grandiose and decaying city in search of a hostel where we can get ourselves sorted and acquire the travel permits needed to cycle across Tajikstan.

While Dankai will prove the most challenging aspect of our trip, it's not the only challenge we don't yet know about. Mostly because we don't want to know everything in advance. For me, there is no interest in a plotting a trip to the nth degree. I want room for interest, excitement, challenge. I do the research – read people's blogs to learn about the hard times, the good times, the summary, the must-knows – like what sort of stove fuel is available. By the time we flew to Dushanbe, I knew there was a doable route with multiple variations we could explore and that was enough. It was time to get real.

***

Four weeks later we are immersed in the mountains and have grown our cycling confidence through weathering thunderstorms and negotiating with internal border guards who beckon us into their stations and stare at our passports upside down for tens of minutes. We have seen wolf footprints and not been eaten by wolves. We have repaired punctured tyres and strengthened our disintegrating pannier racks using rusty nails and lengths of wire scavenged from the side of the road.

On a chilly morning, we cycle over Ak Baital – at 4655m the highest point on the Pamir Highway – with eight Europeans. The Pamirs is a nexus for Europeans cycling overland to China; this road sees one or two groups of cycle tourists a day. "Michael, my legs are made of butter," French Matteo groans as he wobbles up the shingled crest. In the afternoon we coast downhill with a tail wind to find water on the river plain.

"This will do as a campsite," I yell to Chris when I see a cluster of derelict mud-brick buildings, perched on a river terrace above a typical turgid, grey-brown Tajik river braid. We all search for sheltered campsites, peg down every guy line on our tents, and huddle around roaring cookers chatting about our next day of cycling.

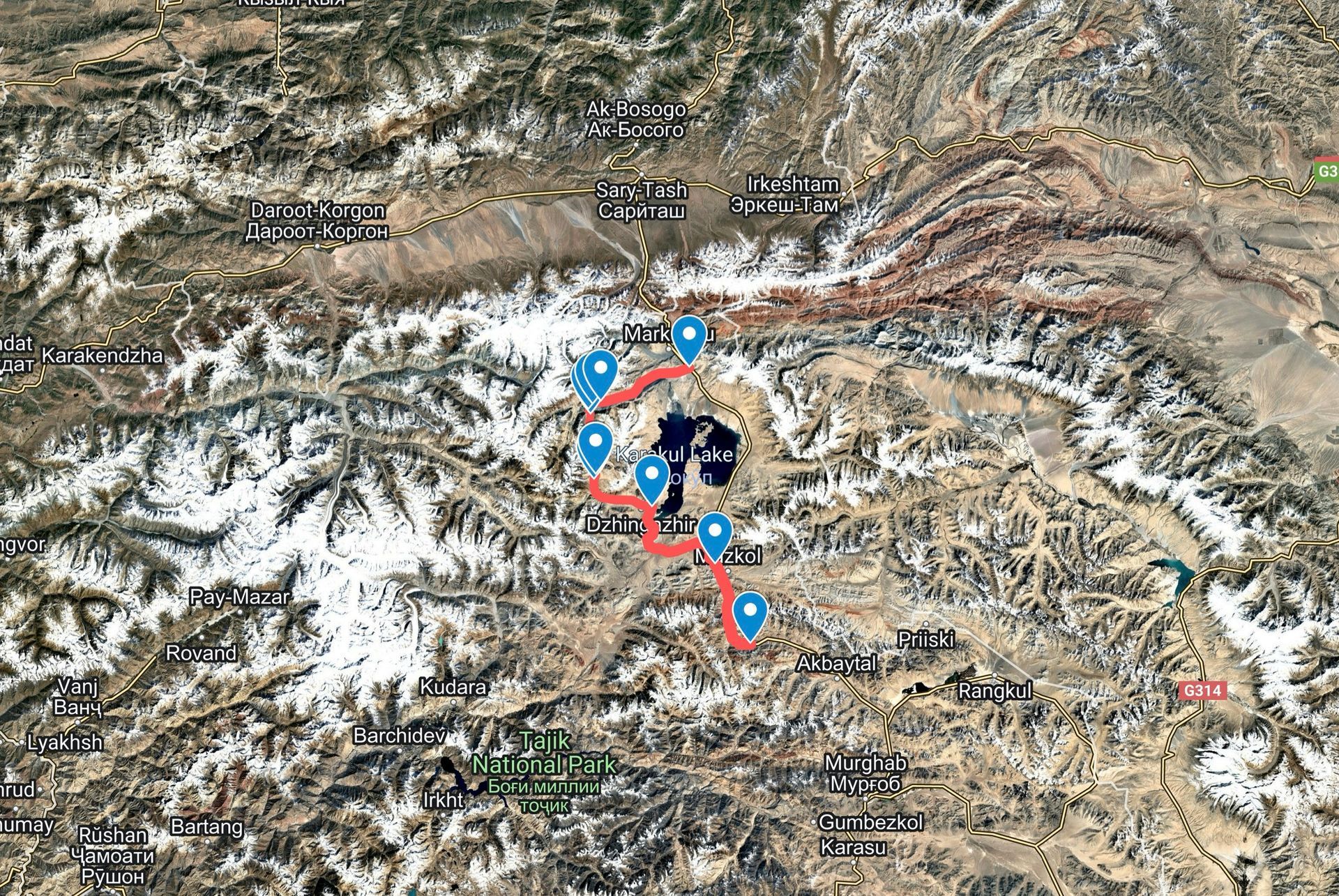

"I'm headed west of Lake Karakol. It looks like you can do this loop." Michael points to two dashed lines on his Android phone screen which mark theoretical vehicle tracks through remote river valleys west of Lake Karakul, the next major landmark on the highway. There's a significant gap in the dashes around a 4600m high point – Karachym Pass. This gap extends over the area labelled 'Dankai', a confluence of three major rivers with their origins in six-seven thousand metre glacier-covered peaks. The 'standard' route follows the highway to the east of Lake Karakul, passing through the town of Karakul, where we'd planned to replenish our food supplies.

Michael was more prepared than us - he downloaded old Soviet topo maps onto his phone before leaving home in Switzerland. They open up possibilities not apparent on the 'chicken map' Chris and I acquired in Dushanbe. Our map was a colourful A3 schematic showing main roads and townships but lacking topo lines or a scale. It made up for these lacks with a decorative camel in the corner that Chris mistook for a chicken because he needed to use reading glasses more often than he wanted to admit.

"We're sticking with the highway," Sue and Julia from Berlin say. Our bikes aren't made for off road and we've got to be in Osh a week from now. "Us too," say Matteo, and Pedro and George from Bulgaria. Their bikes have narrow tyres, unsuited to off road cycling. They are all heavily loaded with front and rear panniers. Matteo reckons he's carrying sixty kilograms, including the alien-faced teddy-bear sitting on his handlebars and his selection of spice jars.

"Are you interested?" Michael looks and Chris and me.

I consider the turbid river braids below us, gaze across sparsely-vegetated yellow-green grasslands to mountain ridges covered in scree and snowfields. I love this landscape. "Sure." I look at Chris, rather than the expanse of undashed terrain on the map. "I'm in," he says.

Next episode next week...