Gold Fever

Chris and his rock containing gold flakes from near Telfer, Western Australia

There’s gold fever in the air in Central Otago as Santana Minerals pushes their gold mining consent forward in the Fast Track application process. But there’s always gold fever in the air in Central – a friend’s friend recently dropped by during his four days of a local gold panning holiday. And gold is worth more than ever before at USD4000 an ounce – no wonder Santana is wanting to mine it.

Why are people so entranced by gold? I’ve had a go at gold panning, both as a child and more recently. We had childhood holidays with my grandparents in Hokitika; Grandad had a gold pan like he had whitebait nets – because he lived on the West Coast. I panned for gold in rivers where we picnicked, and in the sea by Nana and Grandad’s house. I found shiny mica flakes which floated to the surface. I needed to improve my panning skills!

More recently, Chris and I had an afternoon panning for gold in the Shotover with a friend. There were lots of ‘shows’ in the pan – there’s gold in them thar hills. However, my interest rapidly waned when it later came to sifting out the tiny gold dots from the remaining sand. I’ve got the sand mixed with gold in a pill bottle…somewhere.

Gold has long been used by humans as commodity money – a good that can be exchanged for other goods, based on an agreed value. Gold is a physical token of wealth based on perception. Why has gold been perceived as valuable through the millenia? Because it is durable, malleable, sufficiently scarce, beautiful and now historic:

- Durability gives owners surety their currency will remain valuable unlike, say, beaver pelts, or chemical elements which corrode like iron or copper.

- Malleability has allowed gold to be shaped into coins or jewellery for convenient transactions.

- Scarcity is linked to to value – when demand exceeds supply, items become more valuable. Despite all the gold mining that has taken place over millenia, there's only about 20 cubic metres of mined gold on the planet.

- Beautiful is the intangible in the mix. Humans like bright and shiny objects (magpies do, too). Gold is appealing to our eyes and remains so – it doesn’t tarnish.

- Historic - civilisations have recognised gold as currency for thousands of years, giving it more mana as a universal currency. The Lydians minted the first gold coins around 600 BCE.

In the 1800s, many countries linked their currencies to gold in the belief this would facilitate international trade by stabilising currencies. Linking also meant currencies had a ‘real’ backing as their money supply was tied to their gold reserves. This approach limited inflation and established fixed exchange rates. However, it also meant countries couldn’t adjust their money supply in the face of economic downturns. Financial instability after WWI led to countries reconsidering their reliance on gold. The US stopped using the gold standard domestically in 1933, allowing the US money supply to increase to combat deflation and unemployment. Then Nixon ended the international convertibility of the US dollar to gold in 1971.

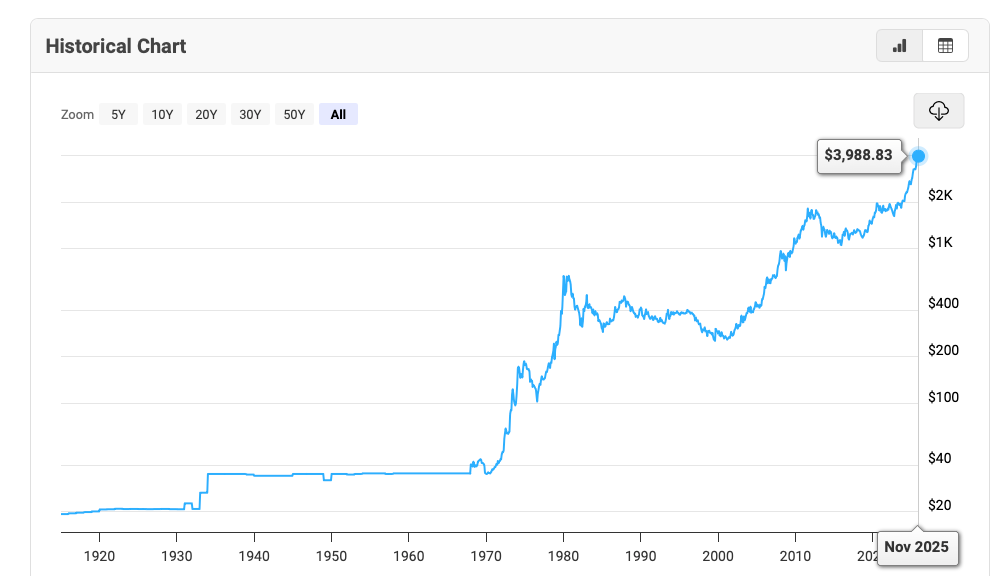

Inflation-adjusted price of an ounce of gold

The price of gold flatlined in the 1930s after an uptick following its delinking from the US dollar. Then the price took off in the 1970s when it was detached from currencies. The abandonment of the gold standard left investors skeptical about the long term value of currencies. Gold ownership was no longer restricted e.g. from 1974 in the US, so anyone could purchase it. Oil shocks in 1973 and 1979 led to economic instability and inflation. Geopolitical uncertainty in the 1970s – the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, tension in the Middle East – boosted gold’s appeal as a safe-haven asset as did the rise of terrorism with numerous hijackings of ships and aircraft. The 1970s demonstrated how gold is appealing in times of crisis.

After the 1970s, gold prices levelled out and even declined slightly around 2000. They didn’t take off again until the early 2000s, when the dot-com bubble burst and there was fear of recession. Then they kept going until 2012, fuelled by the GFC when investors believed currencies, banks, or the world financial system might collapse. The 2010 European Union debt crisis also increased demand for gold.

After another lull, gold prices started rising dramatically again in 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. This led to governments and central banks increasing their gold purchases as a hedge against losing access to foreign currency holdings – they saw Russia’s foreign government bond holdings being frozen. Since 2022, the price of gold has risen steadily, increasing over 50% in 2025 alone. The increases in this period again result from a mix of factors – uncertainty regarding the Trump government’s actions, the rise of exchange-traded gold funds on the internet (buying shares in gold reserves rather than owning actual gold), FOMO. The short summary might be: when there’s instability, gold is in demand. It’s hard to argue against a current feeling of global instability.

The price of gold is driving interest in gold mining, whether alluvial (gold found in river sediment, like the gold our friend was hunting) or placer gold (gold found in rock, which is what Santana wants to mine). When gold is worth more, companies can afford to spend more in the process of exploiting gold resources. As a result, gold deposits that were previously uneconomic to mine become interesting. Our current government sees gold mining as a golden opportunity – how to simultaneously increase jobs and access revenue from royalties to swell government funds. Santana estimates the Bendigo-Ophir mine will create around 350 new jobs and generate $32 million a year in royalties over the thirty-year mining permit it has just been granted (2% of gold sales or 10% of profits, whichever is higher).

Santana says their vision is to: Develop the Bendigo-Ophir project into a world class, long life, environmentally sustainable mining project that will bring generational employment and prosperity to the Bendigo Region. Opponents say the project could be an environmental catastrophe. The big environmental risks from gold mining are contamination from the ‘waste rock’ left over after the gold has been extracted, which is stored in dams’, and escape of the cyanide used to leach gold from rock. You don’t want a Ok Tedi in your region: the lives of 50,000 people were disrupted as a result of 2 billion tons of mine waste being discharged into the Ok Tedi River in Papua New Guinea (the mine was first owned by BHP and now by the PNG government). Nor do you want a collapse to take out your surface operations, cafeteria and local villages as in the Vale tailings dam in Brazil which killed 270 people.

During extraction, cyanide is sprayed onto heaps of crushed ore piled on collection pads. The cyanide trickles down into collection tanks. It is possible for collection pads to leak. In addition, cyanide becomes concentrated in the ‘tailings’ i.e. the rock left over after the mining and extraction process.

Tailings are stored (forever) in tailings dams i.e. physical structures which contain the tailings. Tee dams have impermeable layers on floor and walls to stop leachate escaping. Gold tailings dams contain rocks with high concentrations of toxic elements including arsenic, cadmium, chromium, manganese and lead. The material in tailings dams can escape through leaching into groundwater or dam collapse. Dams collapse through overloading (dam structures are engineered to theoretically hold the weight of material stored in them), or in a major seismic event beyond the strength of the dam perimeter. At Bendigo-Ophir, the dam will sit above the Clutha River so a rupture could release leachate into the river.

Guess what…I reckon both sides of the equation are overblown. There likely won't be as many jobs or as much royalty return as promised, and there also likely won't be a major environmental catastrophe. That’s because both sides of the argument are beefing up their story to get the most traction possible. This doesn’t make decision making easy, however. One can compare the best and worst case scenarios – are 350 jobs for thirty years and NZD1 billion worth a tailings dam collapse? Or one can compare a middling scenario – are 200 jobs for twenty years and NZD500 million worth risk of leakage from the tailings dam into groundwater?

However, the public won’t have to weigh up these matters because Fast Track legislation doesn’t allow for public comment. Investors sigh with relief – experts will debate the issues with social media trolls out of the picture. Environmental activists shout with frustration – when there’s a ‘Drill Baby Drill’ Minister heading a process, can one expect good decisions to be made?

Every human activity has consequences. Our existence alters the nature of our environment. And when there’s gold at stake…the Gold Rush miners gave up their homes, their families and their lives, entranced by the chance of a find. The Otago gold rush lasted five years, similar to gold rushes in the US, Canada, Australia, South Africa. How long will this gold rush last? And what will be left once it ends?