End of a career?

When faced with challenges…daffodils and mountains provide a great backdrop.

This week, the government announced the creation of ‘Research Funding New Zealand’ – a new decision making board which will make most research funding decisions here. I had two initial reactions:

- Does this spell the end of my research funding career? I’ve spent much of the last thirty-five years helping people navigate the funding system and write excellent research funding proposals. I will know nothing about the new system, where one of my points of difference was long familiarity with many aspects of the existing systems. Also, the amount of funding for research is rapidly diminishing under this government and has been diminishing at the rate of inflation for the last eight years. Research organisations are protecting their staff by channelling money to salaries, rather than paying for external contractors. Not to mention the revamp of the system will take time – already funding rounds have been delayed for a year, disappearing the majority of my work.

- Finally, a reduction in the complexity of the NZ funding landscape. I’ve complained about complexity of the funding landscape for over a decade. There are too many different funds creating too many different entities with duplication of bureaucracy wasting considerable sums.

I’ve discovered anyone can become redundant, even self-employed people. If the activity you do becomes redundant, you have the choice of reinventing yourself…the problem being that if you love what you do, you want to keep doing it! I love working with researchers and their interesting research questions, particularly young researchers. I love helping people think through their research questions – it’s like doing puzzles but much better. I love taking in lots of information and delivering a concise and coherent document for other people to read.

Well, bad luck for me, is the final analysis on that front. Like it’s been bad luck for lots of other people who have become redundant through time and is currently bad luck for a lot of researchers. The world owes me neither an income nor a role. Good thing I’ve been growing my music and creative writing activities so I have something to take the place of research funding work. And, as Chris pointed out, I never have enough time to do all the things I love to do.

I admit it’s going to take some more staring at mountains and daffodils, and going for bike rides to deal with this conclusion. And I could be catastrophising…no one else will know the new system any better and I retain my skills in crafting good proposals in collaboration with researchers.

On the wider impact of the changes in research funding – a much more important thing than my personal employment situation – I’m doing plenty of thinking. The proposed simplification could be good…under pretty much any other government in New Zealand’s history. This government is highly interventionist and the new Research Funding New Zealand will consolidate strategy, decision-making power and process under a single ministry (MBIE) and minister. We will no longer have different funding mechanisms where we can compare utility of different approaches (diversity is good in every realm). Everything will be the same, directed by the same minister, with the same cronies.

There’s also a problem with the government’s rhetoric around the funding changes. The coalition is claiming they will “Drive science that grows the economy, supports exporters, tackles environmental challenges and improves health and wellbeing.” Let’s focus on the economic growth because that’s where this government’s heart really lies. If research is going to do anything, including growing the economy, it needs funding. This government is decreasing the available research funding at a rate faster than any government since the research reforms of the 1980s. If they really wanted to increase what research delivers to New Zealand, they would increase funding, as well as streamlining the system.

I read through the NZ Science Media Centre’s commentary on the research funding changes. This commentary has not been picked up by the wider media - New Zealand at large appears disinterested in what’s going on in science and research…but that’s a whole other issue. Summary points from the prominent researchers interviewed include:

- Consolidation of funding could streamline and decrease costs in the funding process.

- Concern about the rigour that will be applied to decision making in future, given poor decision making by MBIE to date.

- Concern decisions will be made by people who don’t understand the process of science and research (so far the entities created in the new research funding system are dominated by business people).

- Concern that lack of funding constrains what can be done, whatever the new system. And because all the changes taking place have to be funded from the existing budget, there is less money to do research than before.

- Concern discovery-driven science is being phased out, in favour of directed research.

Does the government need to fund discovery-driven research? I’m in two minds on this one. While there’s lots of rhetoric that discovery-driven science leads to wonderful serendipitous findings, I have found little evidence that discovery-driven science delivers more meaningful results than directed research. I was excited to see one of the comments from the NZ Science Media Centre article which referred to the recent Nobel prize in economics – the comment said the Nobel was awarded for the researchers' demonstration of how discovery science underpins economic growth. I immediately went to read the summary of the Nobel-winning research and discovered the scientist’s statement was not correct.

The award was made to three researchers. One of them (Joel Mokyr) found increasing the quantum of useful knowledge increases the rate of growth of human society. ‘Useful knowledge' has two parts - propositional knowledge which describes the natural world so we can understand how things work, and prescriptive knowledge, such as practical instructions/drawings/recipes that describe what is necessary for something to work. So there’s plenty of research that might be done that will not have any impact on growth because it doesn’t deliver either type of knowledge.

To explain these two types of knowledge, Ignaz Semmelweis is famous as the ’saviour of mothers’ for reducing maternal mortality in Vienna General Hospital through his finding that, when healthcare workers washed their hands, fewer women died after giving birth (prescriptive knowledge). Doctors were very reluctant to believe this, and Semmelweis had no theoretical basis for his proposition (propositional knowledge). After his death resulting from a beating in an asylum where he was committed after suffering a nervous breakdown (from challenging authority), Louis Pasteur confirmed the germ theory of disease (propositional knowledge) and Joseph Lister used Pasteur’s findings to increase the options for cleaning hands, instruments and medical patients (more prescriptive knowledge).

Pasteur’s work had major impacts, but his research on antiseptics wasn’t serendipitous or discovery-driven. It came from his interest in fermentation for making alcohol. He commented, “In the field of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind.”

As well as describing knowlege useful to economic growth, Mokyr noted that technological development is not the historical norm for humans, rather the opposite is true. For most of human history, there was relatively little growth. According to Mokyr, this is because new ideas did not continue to evolve or lead to a flow of improvements and new applications.

The two other Nobel laureates built on Mokyr’s findings through economic modelling. In contrast to Mokyr’s use of historical observations to comment on the relationship between the sum of human knowledge and growth, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt constructed a mathematical economic model showing how technological advancement leads to sustained growth. They realised that, while economic growth figures appear stable, there is huge churn in companies e.g. in the US over 10% of all companies go out of business each year and a similar number are started. Aghion and Howitt realised this process of ‘creative destruction’ is at the heart of sustained growth.

Aghion and Howitt’s model shows companies with advanced technology protect their new discoveries so they can be paid more than their production costs for their products. The potential to profit from a (temporary) monopoly leads companies to invest in R&D. The longer a company believes its product can remain at the top of the ladder, the more it will invest in R&D.

There is a balance between the forces that decide how much is invested in R&D, linked to the speed of creative destruction and economic growth. Money for investment originates in household’s savings. How much households save depends on the interest rate, which is affected by the growth rate of the economy. So production, R&D, financial markets and household savings are inextricably linked.

Aghion and Howitt’s model can be used to analyse the optimal volume of R&D and economic growth in a free market without political interference. They found the answer is complex because there are two opposing mechanisms:

- Companies investing in R&D know their advantage from a particular innovative product will not last forever because another company will launch a better product. Society values the old innovations because it knows the new innovations are built on old innovations. So society has an interest in subsidising R&D.

- When one company pushes another from the top of the ladder, the new company makes a profit while the old company’s profit disappears. The new innovation may be only slightly better, so company profits may be far greater than socioeconomic gains i.e. investments in R&D can be too large for the benefit, tech development can be too rapid and growth too high. This is a disincentive for society to invest in R&D.

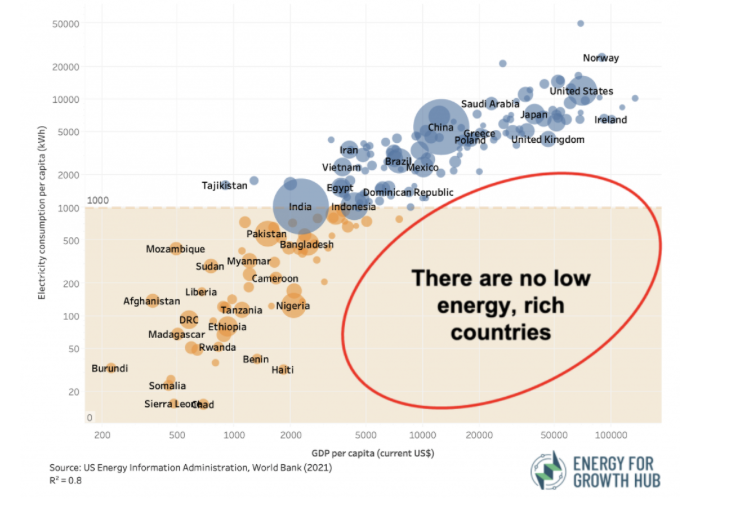

Strangely, there is nothing in the summary of the laureates’ work noting that

energy is core to economic growth. While new knowledge and creative destruction may be at the heart of the rapid technological advancements and economic growth since the 1800s, growth has been based on the use of fossil fuels. GDP is tightly linked with available energy. Whether energy availability is a driver of growth can be questioned, but there is no doubt it is

essential to growth. The lack of mention of such an important aspect of growth concerns me even though I am not an elite member of Nobel Laureate selection panel.

Electricity availability vs GDP in 2021

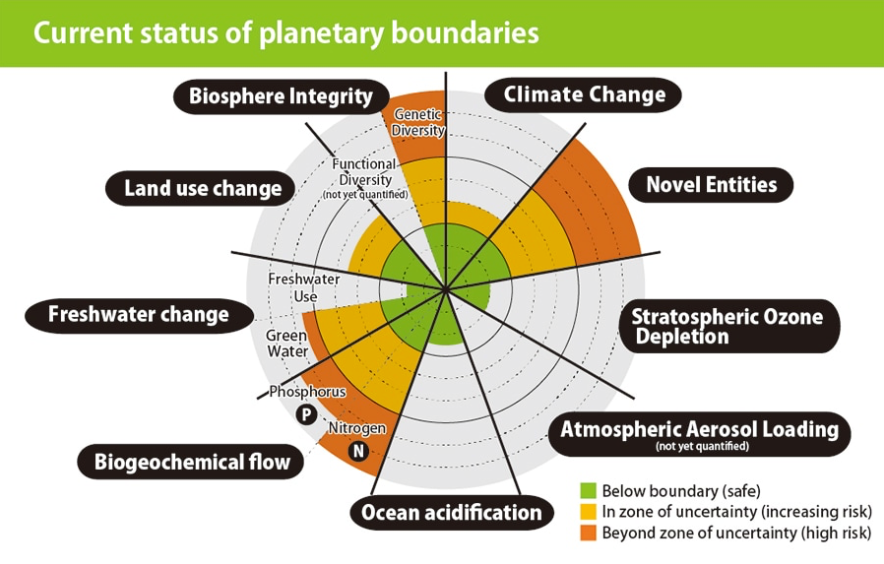

What the summary of the laureates' work does note, however, is that sustained growth is not synonymous with sustainable growth. We all know growth in human endeavours is coming at significant environmental cost with climate change being just one of the major environmental problems we are facing. Of the nine planetary boundaries identified as essential to regulation of planetary environmental health, seven have been crossed beyond the safe zone.

There is no infinite growth in a finite system. Therefore increasing our growth rate is just hastening us to the point when growth will end, and possibly in a way that is very nasty for human beings (as well as many other organisms). So if discovery, or any type of science, is essential to economic growth, we should do less of it!

The laureate summary therefore provides hope from two perspectives. First, it points out that humans have rarely lived in times of economic growth; most of human history has been stagnation. Growth is not essential to human existence or wellbeing (if we consider that at least some of the humans who have lived through history have enjoyed their lives). Second, it demonstrates that slowing investment in R&D will slow growth, which is unsustainable for our planet.

Maybe what our government is doing in minimising science through reducing funding is the right thing although it's being argued completely wrongly?